If the original production of

My Fair Lady was my first Broadway show, in 1961 at age seven (

as I posted here), then

Camelot was my second, in 1962 at age eight.

I even know exactly when my mother took me to the show, since she bought a program and memorialized it on the cover. - "Saturday matinee, September 8, 1962" (black line added digitally to photo).

There was very good reason that this was my second show - the lyricist-librettist/composing team of Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe were following up their megahit (

Fair Lady) and both shows were relatively family-friendly, but with complex adult themes.

Based on British author T.H. White's version of the King Arthur legend,

"The Once and Future King," Camelot tells the story of Arthur and Guenevere's romance and marriage, Arthur's establishment of the Knights of the Round Table as a force for good, Lancelot du Lac's arrival from France to join the Round Table, Guenevere and Lancelot's illicit affair and its destructive force upon Camelot and the ideals of the Round Table.

Among other characters, the two main schemers conspiring to bring down Arthur's rule are his illegitimate son, Mordred, and Mordred's mother, Morgan Le Fay.

Sixty years later,

Camelot is getting the full

Lincoln Center Theater revival treatment -- 30-piece orchestra, Bartlett Sher directing, original Robert Russell Bennett and Philip Lang orchestrations.

I went to a preview performance, three days before opening night, set for April 13, 2023. Lerner's book has been rewritten by Aaron Sorkin; there's a more-diverse cast and there have been a few other tweaks for modern sensibilities, some of which work and some, I think, do not.

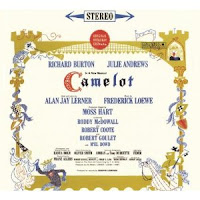

Hearkening back to the original show, one has to understand its impact. Ticket sales were slow until the Ed Sullivan show featured Richard Burton as King Arthur and Julie Andrews as Guenevere singing a couple of numbers.

The score was acknowledged to be extraordinary -- full of wonderful melodies and elegant lyrics -- but critics thought the show couldn't settle on a mood -- lighthearted in the first act, somber in the second -- and Lerner's book was criticized as being too talky and slow.

Nevertheless, the score became so popular that the LP was found in many an American household, the songs played and sung over and over.

The show also rocketed a Broadway unknown - Robert Goulet - to stardom. Although he is the third in the Arthur-Guinevere-Lancelot love triangle, he was listed below Roddy McDowell (Mordred) and Robert Coote (Sir Pellinore) on the album cover.

Goulet was astonishingly handsome, with a rich baritone voice like chocolate and red wine, and he made millions of hearts melt when he delivered the ballad that Lancelot sings to Guenevere, "If Ever I Would Leave You."

My fashion editor mom, Florence De Santis, had interviewed him for her celebrity fashion column, so we went backstage after we saw the show and he autographed that program. I remember him smiling and chatting and being very charming to a little girl.

Camelot also became associated with the three-year administration of President John F. Kennedy, since shortly after his assassination in November, 1963, his widow Jacqueline said her late husband loved the lyrics, "Don't let it be forgot/That once there was a spot/For one brief shining moment/That was known as Camelot."

|

Andrew Burnap as King Arthur

Phillipa Soo as Guenevere,

Jordan Donica as Lancelot

Photo/Joan Marcus |

So - rather a lot of baggage for one show, and

Camelot arrives at Lincoln Center with a lot of anticipation.

From the opening scene, when the courtiers are awaiting Guenevere's bridal carriage at the top of the hill, only to realize it is stopping at the bottom of the hill, creating a confusing new tradition, Sorkin's snappy, sitcom-quick dialog is playing for laughs, which it gets.

One of the courtiers, however, complains consistently that "things are changing too fast," possibly foreshadowing future uneasy changes.

Arthur (Andrew Burnap) drops out of a tree, musing in song that his people are thinking, "I Wonder What the King is Doing Tonight?" Terrified at the idea of his unseen bride, he replies, "He's scared."

Guenevere (Phillipa Soo) runs from her retinue, none too thrilled at the idea of an arranged marriage. She is one tough cookie, showing up in black leather pants, with a pack and knife, yet she also bemoans "The Simple Joys of Maidenhood," in which girls could get a few knights to fight over them before they had to get married. I guess she wasn't wearing that outfit in the carriage and changed clothes going up the hill (?).

When Arthur realizes who she is, he sings of his kingdom's lovely climate and winsome qualities in "Camelot." However, in Sher's staging, Guenevere constantly interrupts his singing with snarky comments, undercutting the song with which Arthur is supposed to be winning her over.

|

Phillipa Soo and Andrew Burnap as

Guenevere and Arthur. Photo/Joan Marcus |

Nevertheless, Burnap and Soo's beautiful singing voices and excellent diction deliver the essence of the first three witty numbers.

One of Sorkin's declared changes to the book was that he was going to "get rid of the magic," to focus on the human relationships.

So, the magician/Arthur's tutor, Merlyn (Dakin Matthews), makes only a brief appearance in the first act. The nymph Nimue is gone, and so is her enchanting song, "Follow Me," that lures Merlyn away from Camelot.

I have to wonder, though, about taking magic out of a mythical person and place, in this era besotted with Harry Potter and accustomed to filmed entertainment that uses computer animation to be even more magical.

Merlyn does get a good Sorkin line, however, as he realizes Arthur's plans - "A powerful man, determined to do good. Things can get dangerous."

Determination of steel characterizes Lancelot, convinced that he's the perfect knight for the Round Table, in the song "C'est Moi." Jordan Donica was out for several performances, unusual for a preview so close to opening night, so at this performance, Lancelot was played by understudy Matias de la Flor. I certainly look forward to hearing his voice develop further, because his control of breath and volume was not up to the task.

Guenevere and the court celebrate May Day with a country festival, a maypole and "The Lusty Month of May," made more obvious by Guenevere's way-off-the-shoulder dress and handsy behavior with the guys. Put off by Lancelot's boastful manner, the queen goads three knights to challenge him at the jousting tournament ("Take Me to the Fair").

Lancelot easily bests two knights, then Arthur challenges him - a plot change from the original, in which Sir Lionel is the last challenger. So here, it's Arthur, not Lionel, who is grievously wounded (Or is he? He gets up pretty fast.) and brought back to life by Lancelot's intense faith and prayer. I suppose it raises the emotional stakes for the trio. It's certainly the first time in this production that Guenevere has shown she cares for him at all.

|

Lancelot (Donica) and Arthur (Burnap)

in combat, as Guenevere (Soo) looks on. |

Seeing Arthur defeated felt unsatisfying to me since it seems Burnap has been playing him as a bit of a wimp, and Guenevere continues her snarky ways.

There's little chemistry between the two, and in a conversation about their relationship, he calls her, oddly, his "friend and business partner."

Dramatically, if two romantic leads just continue to snipe at each other, and there's no heat, boredom sets in. The young woman next to me was shifting in her seat and attempting to read her program in the dark.

Guenevere and Lancelot are supposedly falling in love, but again, little chemistry. But nothing can harm my favorite ballad in the show, Guenevere's conflicted desire to see Lancelot go away - "Before I Gaze at You Again."

Along the way, I realized that the snappy rhythms of Sorkin's dialog didn't jive with the long notes and lush Broadway sound of the score's original orchestrations, which the production proudly cites in its publicity.

Sorkin again brings us down to earth with a Lancelot speech that argues against magic and God -- well, so much for his faith. But Lancelot has to wrestle with his faith, his conscience and his image of himself as a godly man -- as he pursues his adulterous love for Guenevere. In turn, both of them must feel and express great love for Arthur, as husband, as friend, as king, which makes their sin all the more tragic. Unfortunately, the feeling isn't there with enough force.

The second act still turns dark, with the appearance of Mordred. Now we're getting a more nuanced picture of the king. He's made mistakes in his youth. Burnap's performance really shines, as he acquires gravity and seriousness as an older Arthur, wrestling with his ideals and with human nature.

One of the most charming songs, "What do the Simple Folk Do?" where Arthur and Guenevere try to imagine how "ordinary people" cheer up, is staged frustratingly. The final stanza is "they dance," but Guenevere, instead of dancing with Arthur, keeps running from him and their dance lasts just a minute.

Lured away from the castle, Arthur visits Mordred's mother, Morgan Le Fay, a sorceress in the original and here, a scientist -- which makes no sense. Back at the castle, with Arthur gone, Mordred stokes conflict among the knights and Lancelot comes to Guenevere's bedroom. The scenic video design and lighting (by 59 Productions and Lap Chi Chu) are outstanding here, toggling back and forth between Morgan's lair, with branches and stone floor, and the castle, depicted by shafts of light.

The lovers are discovered, Guenevere is arrested, Lancelot fights his way free and she is to stand trial for treason. To my eight-year-old mind, the most thrilling song is here - "Guenevere" -- which, to a galloping, ominous rhythm, details the danger she is in. I accepted the switch to a more-grave second act. Maybe because mom read stories aloud and I read a lot on my own, I knew that life can turn quickly from light to dark, and that something very grown-up and serious was going on.

Arthur's agony is heartbreaking: Adhere to your declared rule of law and you kill the woman you love. Let her go, and you're a hypocrite. Events drive toward an inevitable climax, but Camelot ends on a note of hope.

|

| Burnap as Arthur |

The show is worth seeing for that magnificent score and Burnap's journey as King Arthur. His struggle with his own nature ("I shall have a man's vengeance!"), his ideals and his love are so affecting that I had the tissues out.

I was also reminded of an event that will take place in three weeks - the coronation of another king of England - Charles III. He, too, is exploring, perhaps struggling with, what it means to be a king.

For the other leads, it's a shame that Soo has been directed to make her character unlikable and I had no way of evaluating Donica's Lancelot.

It's a truly bad actor that can't make the most of a great role such as Mordred and Taylor Trensch is a terrific actor, delivering his character's creed, "The Seven Deadly Virtues," with panache. Marilee Talkington is a striking, red-haired Morgan Le Fay and Dakin Matthews embodies old folks' wisdom and comedy in the dual roles of Merlyn and Sir Pellinore.

If you go, just realize that there might be a couple of places in the show where you think, "hunh?"

Footnote: In the sheer-coincidence department -- my father and brother were/are named Arthur and I just discovered that Robert Goulet's granddaughter is named ... Solange.